Another traffic safety advert using cognitive psychology to make a point, though this time with perceptual illusions:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4xW-VAvQvSk

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Monday, October 20, 2008

'Awareness' Test

I was surprised to see this adapted for an advertisement (based on research originally reported by Ulric Neisser, and a more recent version by Dan Simons):

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

German vs. American Higher Education

The Uni here is going through a transformation. Traditionally German universities awarded the Diplom degree as the terminal undergraduate degree (or, in British terms, graduate--graduate students in the US would be called postgraduates in the UK). That is all changing. There will now be a BS and MS available, replacing the Vordiplom (pre-Diplom) and Diplom, respectively. The idea is to have the German system match that being used throughout Europe, and in the US, which would increase the mobility of university students here. Many outside of Germany do not know what a Diplom is, with the best translation being a Masters because of the thesis work required.

This change to, what I know as, the US system is fascinating. First of all, one hundred years ago, German universities were the top in the world and German was the lingua franca of science. Santiago Ramon-y-Cajal, in his Advice for a Young Investigator wrote that one must learn German to have an impact on science--publishing only in Spanish-language journals would have no impact internationally.

Second, the German educational system educated the first generation of American experimental psychologists, with Wilhelm Wundt as the founder of it all. My intellectual ancestors go back to the great German physiologists who most influenced modern cognitive psychology and neuroscience.

Third, some great American universities, such as Johns Hopkins and the University of Chicago, were modeled after the German system. The Diplom is founded on the idea that learning best takes place by doing. That is, one must engage in research to truly become educated about one's field. Johns Hopkins originally granted only graduate degrees because that seemed to be the American equivalent of what the German universities were doing, in contrast to the liberal arts degrees one studied for at Harvard and other such schools at the time. (Interestingly, Hopkins still does not require a Bachelors in order to be accepted into a PhD program.)

Fourth, the standard pedagogical technique in the classroom at places like Johns Hopkins was inspired by the German-style seminars. Again, it is the case of learning-by-doing. Instead of only having lecturers pour information into the brains of the students, through the ears, the seminar was created to have students learn by studying the topics with professorial guidance, and then presenting the overview to their classmates for discussion.

Now my colleagues here are asking me how multiple-choice exams are administered and graded, as the standard oral examinations will be unreasonable in the face of larger course enrollments and lecture-style courses!

Clearly there is something to be said for mobility, particularly in the European Union. However it is strange to see such an important tradition in higher education disappear, particularly one that has been widely emulated and transformed American universities into the research-focused institutions they are today.

Technorati Tags: America, Bachelors, Diplom, European Union, Germany, higher education, Johns Hopkins University, Masters, Santiago Ramon-y-Cajal, science, seminar, University of Chicago, Wilhelm Wundt

This change to, what I know as, the US system is fascinating. First of all, one hundred years ago, German universities were the top in the world and German was the lingua franca of science. Santiago Ramon-y-Cajal, in his Advice for a Young Investigator wrote that one must learn German to have an impact on science--publishing only in Spanish-language journals would have no impact internationally.

Second, the German educational system educated the first generation of American experimental psychologists, with Wilhelm Wundt as the founder of it all. My intellectual ancestors go back to the great German physiologists who most influenced modern cognitive psychology and neuroscience.

Third, some great American universities, such as Johns Hopkins and the University of Chicago, were modeled after the German system. The Diplom is founded on the idea that learning best takes place by doing. That is, one must engage in research to truly become educated about one's field. Johns Hopkins originally granted only graduate degrees because that seemed to be the American equivalent of what the German universities were doing, in contrast to the liberal arts degrees one studied for at Harvard and other such schools at the time. (Interestingly, Hopkins still does not require a Bachelors in order to be accepted into a PhD program.)

Fourth, the standard pedagogical technique in the classroom at places like Johns Hopkins was inspired by the German-style seminars. Again, it is the case of learning-by-doing. Instead of only having lecturers pour information into the brains of the students, through the ears, the seminar was created to have students learn by studying the topics with professorial guidance, and then presenting the overview to their classmates for discussion.

Now my colleagues here are asking me how multiple-choice exams are administered and graded, as the standard oral examinations will be unreasonable in the face of larger course enrollments and lecture-style courses!

Clearly there is something to be said for mobility, particularly in the European Union. However it is strange to see such an important tradition in higher education disappear, particularly one that has been widely emulated and transformed American universities into the research-focused institutions they are today.

Technorati Tags: America, Bachelors, Diplom, European Union, Germany, higher education, Johns Hopkins University, Masters, Santiago Ramon-y-Cajal, science, seminar, University of Chicago, Wilhelm Wundt

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Scientific (and Statistical) Literacy Meet the Press

"Oh, people can come up with statistics to prove anything, Kent. 14% of people know that."

~Homer Simpson

Often when reading the newspaper I am flummoxed by the treatment of numbers. Here is a recent example from the New York Times/ International Herald Tribune:~Homer Simpson

"The polls, taken for a local newspaper, use small samples, 500 people, limiting their usefulness as a gauge of popular sentiment in a city of one million."

Although numbers are often cited to provide evidence, they are often taken out of context or, just as bad, not given a context. Although editors seem keen to check the accuracy of quotes or the reliability of sources, they seem to skim over any mention of numbers. This is true of both op-ed opinion pieces and front-page investigations.

Besides teaching a research methods and statistics course, I also once worked for a public opinion polling firm, so the above quote struck me as incorrect on more than one level. So I wrote to the journalist:

"Your article on the mosque in Cologne misrepresents what is scientifically acceptable regarding sample sizes and population size. The whole point of a sample is to gauge the opinion of the greater population by taking advantage of probability. A sample of 500 is more than sufficient to do this--one need not ask every single inhabitant to infer their opinions! A properly created sample that randomly selects members of the population and does not seem to choose accidentally one segment of the population (e.g., the 500 polled all happen to be Turkish) is an excellent way to gauge the opinion at large with a confidence interval of +/- 4% to 5%. Unfortunately you do not provide the poll's results, just a summary that a majority support the mosque, so it is hard to apply the confidence interval here. The Times really should consider having a 'numbers czar' (maybe a colleague from the Science Times?) available for consultation on this and other issues that involve statistics and scientific literacy. The offending quote: 'The polls, taken for a local newspaper, use small samples, 500 people, limiting their usefulness as a gauge of popular sentiment in a city of one million.'"

The journalist was kind of enough to run a correction and write back to let me know:

"Your point was legitimate, as is your suggestion that we do a better job of vetting these issues before they get into print. We ran a correction on Saturday on the size-of-sample issue.

Best, Mark"

Here is the correction, with a link to the original article:

"An article on Thursday about a German backlash against plans for a mosque in Cologne, known for its Gothic cathedral, referred incorrectly to the size of polls taken for a local newspaper there, assessing the popularity of the mosque. The sample of 500 people was sufficient for a scientific poll; that sample was not "small," nor did its size limit the poll's "usefulness as a gauge of popular sentiment in a city of one million." (Go to Article)"

First, my thanks go to Mark for being open to the comment, and for having a correction appended. Second, I really do hope this paper and others consider having a staff member edit articles for numerical clarity. The readership deserves to have all the news be fit to print.

Technorati Tags: New York Times, International Herald Tribune, science, scientific literacy, statistics, Mark Landler, sampling, public opinion, Homer Simpson, Cologne, mosque

Monday, July 2, 2007

Neuroscience or Pseudoscience? The Age of "Check Spelling"

In writing a forthcoming blog, I noticed that the automatic spell-check picked up this problem, and offered a wonderful suggestion:

I do not know who is responsible for this suggestion, but it has also arisen when I have typed an email as well! I think Google might be behind this...

I do not know who is responsible for this suggestion, but it has also arisen when I have typed an email as well! I think Google might be behind this...

Technorati Tags: neuroscience, pseudoscience, science, spell-check, Google

I do not know who is responsible for this suggestion, but it has also arisen when I have typed an email as well! I think Google might be behind this...

I do not know who is responsible for this suggestion, but it has also arisen when I have typed an email as well! I think Google might be behind this...Technorati Tags: neuroscience, pseudoscience, science, spell-check, Google

Labels:

Google,

neuroscience,

pseudoscience,

science,

spell-check

"Psychology Sets" for kids--why stop with Chemistry?

Remember the old Chemistry sets? They once actually came with corrosive and explosive powders that allowed many kids to discover and destroy. Now, they are a bit toned down. We were looking to get our daughter a microscope and Grandma gave her one with one of these new chemistry sets, too. Beware the wonders and danger of .... gelatin. It's a start. Some of the experiments are pretty time-consuming for a kindergartener.

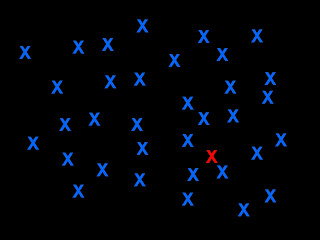

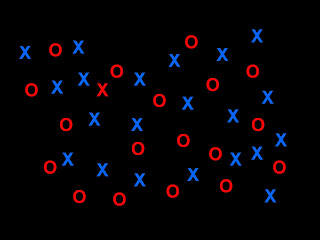

One evening she was asking to do one of these "spare-a-mints" (it is hard to correct pronunciation when it is that cute) but it was too close to bedtime to complete one. Then it occurred to me that she could do a small version of a "daddy experiment" and still get to bed on time. The Psychology Set! I made a quick, cartoon version of four different instances of visual search, based on Anne Treisman's seminal work from 1980. The target was always the same, a red X. Here it is, outlined in yellow.

The only thing that changes are the nontargets, or distractors. The other two letters are the types of nontargets she saw. The first is the blue X, and the other is a red O. So her job was (and now your job is!) to find the red X. To emulate her experience keep a clock nearby and see how many seconds it takes. (If you do not find the target after awhile, you are allowed to stop looking.) Ready? Go!

Found it? Good. Now look for it again here:

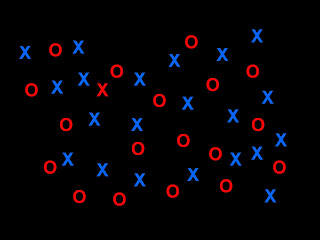

OK, that was a bit tricky. No target there. Try again here:

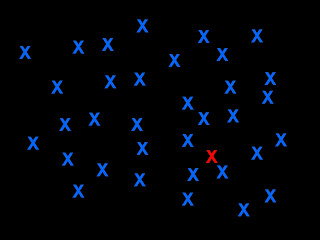

Found it again? One last time, where is it here:

All done! Afterwards I plotted Isabella's data (averaged across two attempts at each trial type) like this:

When the red X is the uniquely colored item it can be found quickly. When it is absent, it takes a bit longer to check and make sure it is not there. However, when there are also a bunch of red Os present, one has to look for the combination (or, conjunction) of red and X to find the target because there are other red items and other Xs, but only one red X. That takes a bit longer. It takes even longer when it is absent because it is harder to make sure it is not there when there are both other Xs and other red things there.

Isabella immediately took up the idea that it was easier for her brain to find the only red thing and harder when it was not there and when there were other red things to "trick" her--she at first pointed at several red Os before finding the red X. (A nice example of searching through just one subset of the nontargets...) And she wanted to keep searching again and again, like a homemade "Where's Waldo" (or, one German version (I think there is another one, too), "Wo ist Walter"). It's nice that she is actually interested in what I did for my dissertation!

Technorati Tags: Anne Treisman, kids, psychology, science, visual search, dissertation, Where's Waldo? experiment

One evening she was asking to do one of these "spare-a-mints" (it is hard to correct pronunciation when it is that cute) but it was too close to bedtime to complete one. Then it occurred to me that she could do a small version of a "daddy experiment" and still get to bed on time. The Psychology Set! I made a quick, cartoon version of four different instances of visual search, based on Anne Treisman's seminal work from 1980. The target was always the same, a red X. Here it is, outlined in yellow.

The only thing that changes are the nontargets, or distractors. The other two letters are the types of nontargets she saw. The first is the blue X, and the other is a red O. So her job was (and now your job is!) to find the red X. To emulate her experience keep a clock nearby and see how many seconds it takes. (If you do not find the target after awhile, you are allowed to stop looking.) Ready? Go!

Found it? Good. Now look for it again here:

OK, that was a bit tricky. No target there. Try again here:

Found it again? One last time, where is it here:

All done! Afterwards I plotted Isabella's data (averaged across two attempts at each trial type) like this:

When the red X is the uniquely colored item it can be found quickly. When it is absent, it takes a bit longer to check and make sure it is not there. However, when there are also a bunch of red Os present, one has to look for the combination (or, conjunction) of red and X to find the target because there are other red items and other Xs, but only one red X. That takes a bit longer. It takes even longer when it is absent because it is harder to make sure it is not there when there are both other Xs and other red things there.

Isabella immediately took up the idea that it was easier for her brain to find the only red thing and harder when it was not there and when there were other red things to "trick" her--she at first pointed at several red Os before finding the red X. (A nice example of searching through just one subset of the nontargets...) And she wanted to keep searching again and again, like a homemade "Where's Waldo" (or, one German version (I think there is another one, too), "Wo ist Walter"). It's nice that she is actually interested in what I did for my dissertation!

Technorati Tags: Anne Treisman, kids, psychology, science, visual search, dissertation, Where's Waldo? experiment

Labels:

Anne Treisman,

dissertation,

experiment,

kids,

psychology,

science,

visual search,

Where's Waldo?

Seeing with your ears?

Here is a little insight into the sorts of experiments I do.

My previous research has mostly focused on the brain finds things visually. For example, how we can find an apple mixed in with other fruit (plus an example of how neurons in the parietal lobe might respond when faced with such a task, from a mini review in J Neuro):

Nowadays I have moved beyond vision to take a look at our other senses, such as how we hear and feel the world, and in particular, how all of this visual, auditory, and tactile information comes together. There are two ways we are doing this. First, we are using a program designed to aid the blind by transforming images into sound called The vOICe. The hope is that, with sufficient training, this device could allow the blind to "see" again, but by using their ears to receive visual-spatial information about the world. Here is what this basically looks like from a NY Times Magazine article on Peter Meijer's device:

(This picture tries to show how a small spy camera takes a picture of the area in front of the user, then transforms the picture into a soundscape. With practice one can learn to interpret these soundscapes in terms of what objects are in the field of view, and where they are, and in a sense "see" again. That is the end-goal at least!)

Secondly we are also studying synaesthesia (also spelled synesthesia), which is a special "cross-wiring" in the brain that certain people have that allows them to perceive something through a different modality than normal. For example, some persons see colors when they hear music. Others always see black-on-white text like this in different colors that are not there such as you see here. Both of these routes will allow us to better understand how the brain puts all of this information from different sources together into one coherent experience.

Technorati Tags: Journal of Neuroscience, New York Times Magazine, science, sensory substitution, synaesthesia, synesthesia, The vOICe, visual search

My previous research has mostly focused on the brain finds things visually. For example, how we can find an apple mixed in with other fruit (plus an example of how neurons in the parietal lobe might respond when faced with such a task, from a mini review in J Neuro):

Nowadays I have moved beyond vision to take a look at our other senses, such as how we hear and feel the world, and in particular, how all of this visual, auditory, and tactile information comes together. There are two ways we are doing this. First, we are using a program designed to aid the blind by transforming images into sound called The vOICe. The hope is that, with sufficient training, this device could allow the blind to "see" again, but by using their ears to receive visual-spatial information about the world. Here is what this basically looks like from a NY Times Magazine article on Peter Meijer's device:

(This picture tries to show how a small spy camera takes a picture of the area in front of the user, then transforms the picture into a soundscape. With practice one can learn to interpret these soundscapes in terms of what objects are in the field of view, and where they are, and in a sense "see" again. That is the end-goal at least!)

Secondly we are also studying synaesthesia (also spelled synesthesia), which is a special "cross-wiring" in the brain that certain people have that allows them to perceive something through a different modality than normal. For example, some persons see colors when they hear music. Others always see black-on-white text like this in different colors that are not there such as you see here. Both of these routes will allow us to better understand how the brain puts all of this information from different sources together into one coherent experience.

Technorati Tags: Journal of Neuroscience, New York Times Magazine, science, sensory substitution, synaesthesia, synesthesia, The vOICe, visual search

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

Seeing with another's perspective

I have been fortunate for the past few days to share the company of a blind person that is participating in our research. Just walking and talking with her opens up new ways of "looking" at where I walk, how I talk, and what I notice through my other senses.

Walking: Offices, houses, hallways, and sidewalks are all cluttered! There are so many objects to be avoided, steps to navigate, branches to duck under, and cords to step over.

Talking: I use the words see, look, and picture in normal conversation to a high degree. It makes sense--we are usually either using our visual system or instructing someone else to do so as well.

Hearing: Many stoplights have no auditory tone accompanying the walk signal. Some are equipped with vibrating units, but many of those do not work. However, if there is traffic, one can hear the direction of the cars moving, and anticipate the likely signal for crossing a street. If the streetlight has a walk signal that is not coordinated in that way (such as when there is a left-hand turn green arrow and the walk signal is red), then that can be a challenge.

The guide dog gets breaks of course to run around on the grass, play, and use the facilities. Careful listening can be pretty revealing of not only where the dog is, but what it is doing. Rolling around on the grass makes the tags jingle quite a bit, while running around is heard with the heavier footsteps.

Touching: While walking I can notice the surface below my shoes even through the fairly thick sole and two pairs of socks (yes, two, but that is another story). The change from brick walkways to a sort of cobble-stone parking lot to concrete are something that can be noticed a bit, and provide cues to the location.

Smelling: I have allergies to some pollen right now, so my nose is sort of useless.

Jose Saramago (his books are great! read them!) wrote a very good novel called Blindness (and an accompanying "sequel" of sorts called Seeing, also good and a very interesting idea for political activism). It was revealing of human nature at both its best and worst, and a page turner (sometimes a stomach-turner as well). I recently read a review that pointed out the bias in the novel that arises from having the heroine be sighted, and helping some people who suddenly (and inexplicably) became blind. Why wasn't the heroine a person who has been blind from birth, and would best know how to navigate a world in that way? I think this choice of Saramago's (if it was a "choice" in the conscious sense of the word) is probably a common sighted bias, but perhaps if he spent some time seeing the world without eyes, he would have chosen differently.

Technorati Tags: blindness, Saramago, science, sensation

Walking: Offices, houses, hallways, and sidewalks are all cluttered! There are so many objects to be avoided, steps to navigate, branches to duck under, and cords to step over.

Talking: I use the words see, look, and picture in normal conversation to a high degree. It makes sense--we are usually either using our visual system or instructing someone else to do so as well.

Hearing: Many stoplights have no auditory tone accompanying the walk signal. Some are equipped with vibrating units, but many of those do not work. However, if there is traffic, one can hear the direction of the cars moving, and anticipate the likely signal for crossing a street. If the streetlight has a walk signal that is not coordinated in that way (such as when there is a left-hand turn green arrow and the walk signal is red), then that can be a challenge.

The guide dog gets breaks of course to run around on the grass, play, and use the facilities. Careful listening can be pretty revealing of not only where the dog is, but what it is doing. Rolling around on the grass makes the tags jingle quite a bit, while running around is heard with the heavier footsteps.

Touching: While walking I can notice the surface below my shoes even through the fairly thick sole and two pairs of socks (yes, two, but that is another story). The change from brick walkways to a sort of cobble-stone parking lot to concrete are something that can be noticed a bit, and provide cues to the location.

Smelling: I have allergies to some pollen right now, so my nose is sort of useless.

Jose Saramago (his books are great! read them!) wrote a very good novel called Blindness (and an accompanying "sequel" of sorts called Seeing, also good and a very interesting idea for political activism). It was revealing of human nature at both its best and worst, and a page turner (sometimes a stomach-turner as well). I recently read a review that pointed out the bias in the novel that arises from having the heroine be sighted, and helping some people who suddenly (and inexplicably) became blind. Why wasn't the heroine a person who has been blind from birth, and would best know how to navigate a world in that way? I think this choice of Saramago's (if it was a "choice" in the conscious sense of the word) is probably a common sighted bias, but perhaps if he spent some time seeing the world without eyes, he would have chosen differently.

Technorati Tags: blindness, Saramago, science, sensation

Tuesday, June 19, 2007

Pondering the blog commitment

I like blogs that post on a regular basis about everything from mundane daily activities to philosophical thoughts to tips on living in a strange new place to describing new science results to discussing new, interesting books. And more. The key part is the regular basis, which is not an easy commitment when other things in life are clamoring for attention. I almost started a blog for a job website about life as a postdoctoral scientist, expatriate, parent, and soon-to-be-job-seeker. Among other things. This may be the place for that.

The title comes from the question I most often get here--"Why would an American come to Europe? Everyone wants to go the other way!" Well, I am happy to do my part to reverse the "brain drain", because some great, creative research is being done here.

In the meantime you can learn a bit more about that research from the links on my web page:

http://mproulxjhu.googlepages.com/

Technorati Tags: blogging, expat, science

The title comes from the question I most often get here--"Why would an American come to Europe? Everyone wants to go the other way!" Well, I am happy to do my part to reverse the "brain drain", because some great, creative research is being done here.

In the meantime you can learn a bit more about that research from the links on my web page:

http://mproulxjhu.googlepages.com/

Technorati Tags: blogging, expat, science

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)